Exclusive Story by WeirdKaya – Proper accreditation to WeirdKaya and consent from the interviewee are required.

Established in 2011, DIB, also known as for Deaf In Business, was built on a simple but radical idea, which is to show that deaf individuals can thrive in an industry often seen as heavily reliant on verbal communication.

Dr Allen Tay is the founder of DIB Restaurant and has spent the last 15 years employing deaf individuals in the food and beverage (F&B) industry.

Drawing from his early experience in the 1980s when he was involved in setting up a KFC outlet in Jalan Imbi staffed largely by deaf employees, Tay realised that employing deaf staff was never the main issue.

“A deaf staff member is just like any other staff They don’t speak, but they have body language and smiles. And honestly, that matters more in customer service,” he explained.

That realisation became the foundation of DIB, which officially opened its doors on Jan 1, 2011, with five deaf women as its pioneer staff.

Struggles faced by DIB

For Tay, DIB is more than a restaurant. “It’s a calling. Without that, I wouldn’t have been able to sustain this for 15 years,” he said.

When the Covid-19 pandemic hit, things nearly fell apart. Businesses that once supported DIB collapsed, forcing Tay to make a tough decision.

“Instead of closing DIB down, I decided to turn it into a non-profit organisation and introduced a profit-sharing model where earnings are distributed among the staff each month.

“It stopped being about money and became about staying true to what DIB stands for.”

Rejected from the start

According to Tay, one of the biggest barriers deaf individuals face isn’t their ability issues, but public perception of people like them.

“When employers see someone who’s deaf, the first thought is always ‘How do I communicate with them?’

“Because of that, many don’t even pass the first round of job interviews. Some even get rejected the moment employers realise they’re deaf.

“This is why DIB exists. If we can survive 15 years running a business with deaf staff, why can’t others hire them?” Tay noted.

He added that deaf staff are often judged more harshly than people with visible physical disabilities as their way of communication is unfamiliar to employers.

Building a restaurant based on inclusion

Rather than forcing deaf staff to adapt to a hearing-centric system, DIB redesigned the system itself.

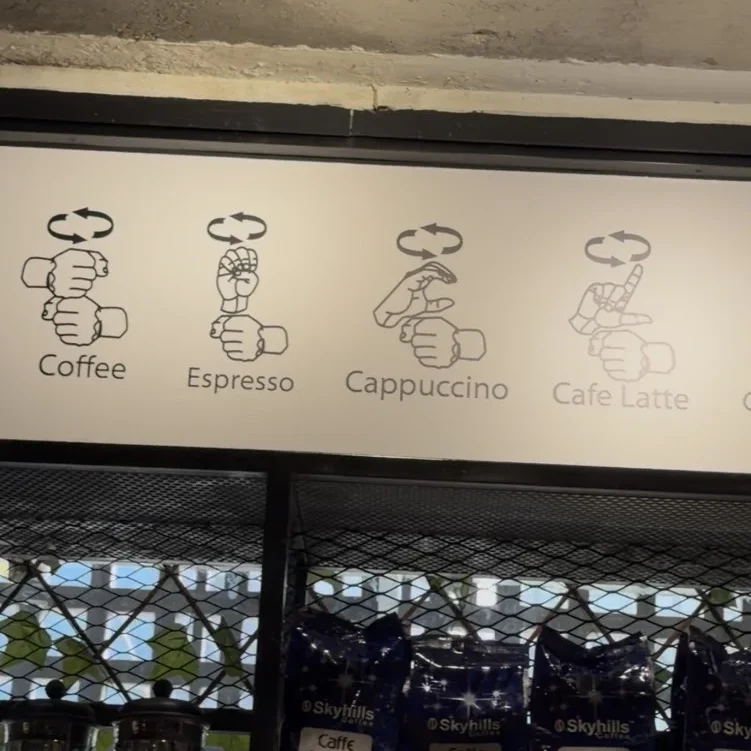

Menus are simple and visual, allowing customers to clearly indicate what they want. Orders are placed at the counter instead of tables to minimise confusion.

As for the POS system, it uses dual screens so customers can confirm their orders visually before paying. For special requests, customers will write them on a whiteboard.

“Everything is designed to reduce errors and reduce stress for both the staff and customers.

“Payments are largely cashless to avoid mistakes involving small change, and regular customers have grown comfortable with the flow.

“For first-timers, staff will provide a simple sign language handout, teaching them basic signs like the alphabet or how to say “thank you”. This turns a potential communication barrier into a learning experience,” said Tay.

From barista to cashier

One of the moments that still amazes Tay is watching how some of his staff surprise him with how quickly they grow.

“Some are fast learners, some are slower. So we adapt. Those who need more time may focus on fixed tasks like customer service.

“At the end of the day, the important thing is that everyone is supported,” he explained.

Over the years, Tay has seen deaf staff pick up complex skills like latte art, multitasking across stations, and even managing entire workflows – something many employers never expect when they see a deaf job applicant walk in.

Training at DIB is mostly done through on-the-job coaching, with chefs and baristas guiding staff step by step. In the early days, Tay even hired a barista champion to train deaf baristas, who picked up the skills within a month.

“We train them to be multi-skilled so that one day, if they want to start their own business, they can run it themselves.”

At one point, staff even wore superhero-themed T-shirts as part of their uniform, reinforcing the idea that they are capable and strong.

Seeing his staff gain independence, buying their own phones, building stable lives, and even getting married has been one of the most fulfilling parts of the journey.

How the community helps DIB carry on

Today, DIB operates from Menara Gamuda, relying heavily on the weekday lunch crowd between 12 pm and 2.30 pm, a narrow window that Tay admits is challenging.

Still, he remains hopeful.

“With continued support from the community, we can keep this going for another 15 or even 20 years.

“At the end of the day, we’re just giving disabled people a chance, and trusting that they’re more than capable.”

Exclusive Story by WeirdKaya – If you wish to reproduce this story, please ensure that you obtain consent from the interviewee to maintain factual accuracy and avoid the potential spread of misleading information.

If referencing or using any information from our story, we kindly ask that proper credit is given, along with a backlink to WeirdKaya, as acknowledgment of the efforts made by our editors in sourcing and conducting interviews.

READ ALSO: